- This event has passed.

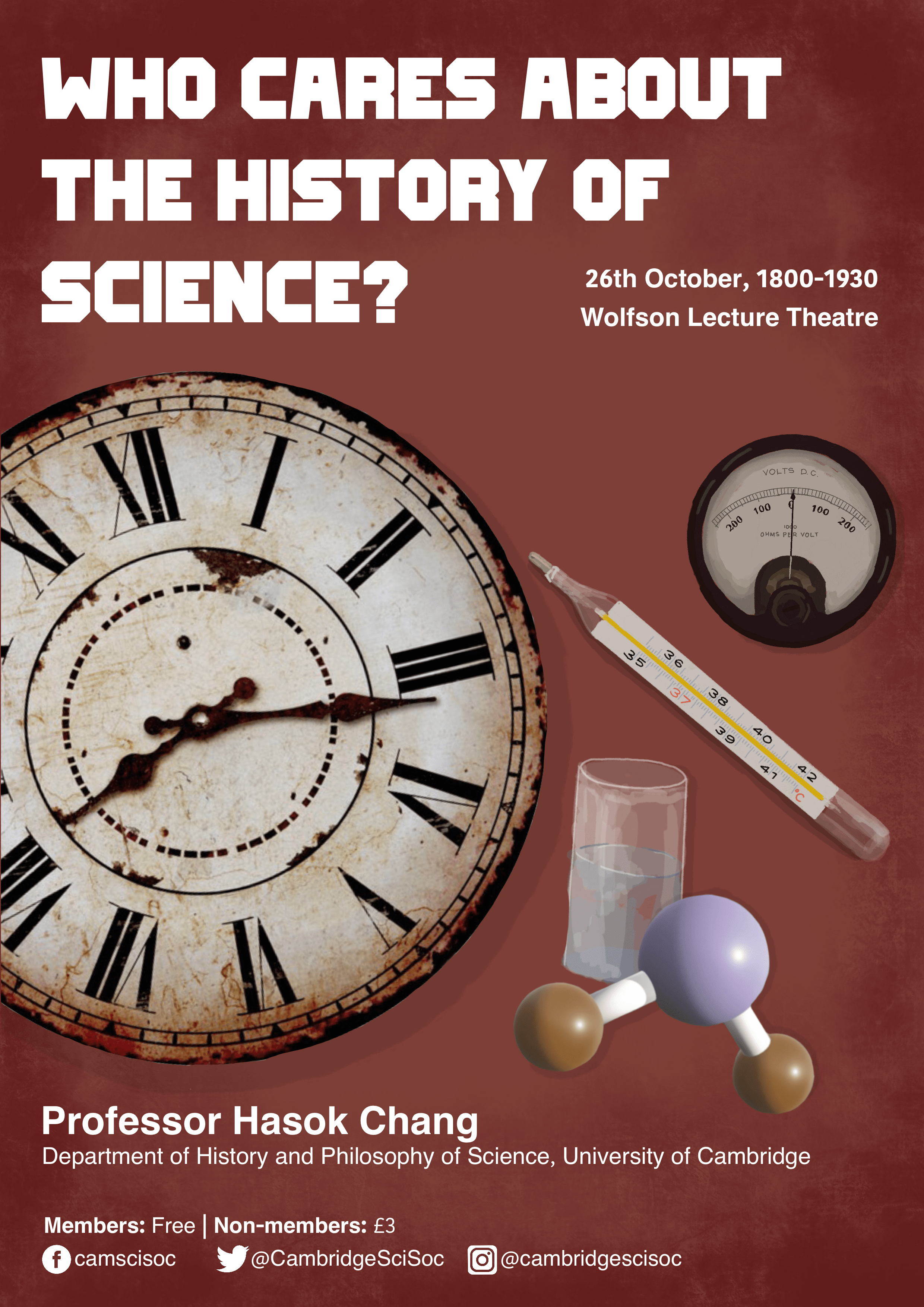

Who cares about the History of Science? – Professor Hasok Chang

26 October 2021 | 18:00 - 19:30

Event Navigation

Abstract

While scientists celebrate certain parts of past science, they disregard other parts as misguided and not worth remembering. The history of science presented in science textbooks tends to be a picture of past heroes who anticipated modern knowledge, such as Galileo, Newton, Darwin and Einstein. But there is also a very different role for history, which is to help us appreciate valuable parts of past science that current scientists do not remember and celebrate. By paying attention to the ‘losers’ in the history of science we can actually learn much that is scientifically valuable. Through historical work we can recover forgotten ideas and phenomena, and a further examination of such recovered items can even lead to new scientific knowledge. Looking at history with full respect for the past scientists, we can recognize that the scientific common sense of today was once the subject of controversy and exciting cutting-edge research. Going back to early periods of science with this kind of historical perspective can awaken a sense of fascination in the familiar aspects of nature, and help us instill a love of science in students and the general public. I will substantiate these claims with illustrations from my work on the history of temperature and thermometry (Inventing Temperature, 2004), the basic atomic composition of matter (Is Water H2O?, 2012), and early electrical instruments and theories (How Does a Battery Work?, forthcoming).

Speaker spotlight

Professor Hasok Chang is in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge.What is your specialization?

History and philosophy of the physical sciences

A short summary of your current research topic

Currently I have two major projects. One is the early history of batteries, going back to Volta’s invention published in 1800. It was really easy to rig up batteries (Volta just used plates of two different types of metals, and pieces of paper soaked in salt water, piled up in alternating layers), but really difficult to understand how they worked. This is understandable given that these early scientists didn’t even have the concepts of electrons or ions as we know them, for about a hundred years after batteries were invented. Even today there are some intriguing questions remaining about these early batteries. My other project is more philosophical, trying to introduce pragmatism seriously into the philosophy of science. The general goal is to make sense of how it is that scientific knowledge grows, without pretending that we are approaching some absolute truth.

What made you decide to pursue research?

I have always wanted to study science because I loved learning about nature and wanted to understand everything. So research was a natural thing for me to go into. How I ended up with my particular field of work is more complicated. I started out wanting to become a theoretical physicist, but during my undergraduate study I realised that the reality of scientific training (problem sets and student practicals) didn’t excite me. I found that most of the questions that I wanted to pursue were considered “philosophical”, and luckily I discovered that there was a field called the philosophy of science.

What would be your advice to aspiring researchers?

Being able to have research as a career is a most wonderful privilege. Go into it only if you can find an area of work that you truly love, and enjoy every moment of it. Don’t become a researcher just because you are cleverer and better than others. The only other reason to devote yourself to research is to solve urgent practical problems facing humanity. But even then, you’ll find that you can’t keep up a life of research very well unless the problems you are tackling really fascinate you.